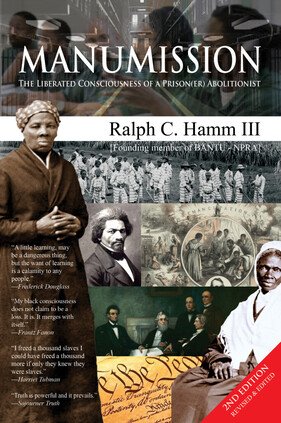

by Ralph C. Hamm III

(Paperback, 6 x 9, $14.95, 230 pages)

Fully revised and edited 2nd edition of Manumission: The Liberated Consciousness of a Prison(er) Abolitionist by Ralph C. Hamm III, is a remarkable book. It is not only an exemplar, presented as eight lessons, for teaching black history but more importantly it is a pathway for all people of color to reclaim their own history, liberation, and consciousness. Ralph’s own life is not only one of personal tragedy, criminal injustice, and prison brutality, but the true expression of the human spirit to obtain manumission in its fullest sense. Ralph was one of the founders of the nation’s first certified prisoners’ union (National Prisoner Reform Association), and one of the driving forces behind the Black consciousness movement in Massachusetts’ prisons (BANTU). With almost 50 years in prison for a non-capital crime committed as a teenager, his leadership and political activism in prison reform has been met with punishment and repeated denials for parole. His struggle for prisoner rights is the articulate voice of a politically conscious prisoner and needs to be heard by everyone.

REVIEW

“Manumission is an important contribution to a people’s history of racial and ethnic domination in Massachusetts, which still casts a long shadow over our collective psyche. Using his own experiences and a wealth of background information, Hamm traces the unfolding development of slavery from its origin here in 1641 to its modern prison-industrial version. Read this book at the risk of losing your illusions of how much progress we have made!”

—George Katsiaficas, activist and award-winning author. His most recent book is Asia’s Unknown Uprisings.

INTRODUCTION

As I moved into my third year of service upon my court-ordered-1969-second-degree life sentence to the Massachusetts Correctional Institution (MCI) located in South Walpole, Massachusetts; I had the distinct honor and privilege to assist in the founding of Black African Nations Toward Unity (BANTU). I was not yet twenty-two years of age.

I, along with black prisoners, Jack Harris, Henry Cribbs, Donald Robinson, Ronald Penrose, James Hall, James McAllister, Raymond White, Charles (2X) McDonald, Alphonso Pinckney, Sam Nelson, and Solomon Brown, comprised the cofounding internal board of directors of BANTU.(1)

We had banded together to embark upon an historic mission: to disseminate the life-saving benefits of black consciousness to the African American prisoners held captive within the walls of Walpole prison. Our singular mission was soon to evolve into an effort to resuscitate the entire Walpole prisoner population (black, white, and Hispanic) through an infusion/transfusion of cultural history and innovative educational concepts, utilizing the flexible format of the National Prisoners Reform Association (NPRA)—effectively a union for prisoners—as our springboard.

Later in the year 1972, I was fortunate to become one of the first internal board of directors for the MCI-Walpole NPRA via an election held by the general prisoner population. As a result of that election, I became one of the organization’s first co-vice presidents. At the outset, the NPRA was a prisoner-elected umbrella organization designed to channel human and other valuable resources to the various, and diverse, prisoner self-help programs existing within the prison.(2)

The NPRA evolved into the recognized grievance negotiator for MCI-Walpole prisoners as well as their collective bargaining agency. The NPRA board of directors determined that the organization had to place itself upon equal footing with the prison guard’s union in an effort to be taken seriously in our transition from merely slaves, to scale paid workers. So, toward that end, we moved to be certified as a worker’s union with the State Labor Relations Commission. A full version of that story is in print.(3)

We of BANTU considered ourselves “abolitionists,” but not in the traditionally recognized historical sense. Our definition of the work of a modern day abolitionist was to free those mentally enslaved through education and cultural awareness. To that extent we would embark upon a quest to deliver our brethren from the bonds of perpetual mental slavery. Prison abolition came later, by way of discussions with Reverend Edward Rodman,(4) and in pursuit of NPRA’s ultimate ambition.

This, then, is a true account of the state’s imprisoned black slaves and their search for their lost identity . . . for manhood and what my stance as a modern day abolitionist has taught me about my servitude.

To fully appreciate and understand the lessons that both BANTU and NPRA learned in Massachusetts as self-professed abolitionist organizations, and how I consciously evolved, in particular as a “runaway slave,” I must return to the history lessons in the black history course mentored by David Dance(5) in Walpole prison between the years 1972 and 1973. I will return to 1638 in the Baystate, and to the origins of the slave trade in America, as well as return to the 1830s-1850s slavery abolition movement in this country. This is necessary to establish a backdrop for Massachusetts’ role in creating, sustaining, and perpetuating that system of chattel slavery that has become the underpinnings of America’s prevailing institutions. I must also draw parallels to today. For only by way of tracing the steps back to the past could I obtain a clear view of the present and secure a proper outlook for the future.

In American society, a number of factors hinder the evolution of consciousness, or insight, toward a clearer vision of the “self.” The method by which children are educated, in many ways, restricts their capacity to truly learn and hinders their creativity. Consequently, young people often experience the struggle for material survival resulting in frustration and resentment. In adulthood, this frequently leads to a variety of compensatory, addictive, and compulsive behaviors. The result is the persistence of social and political oppression, cultural and ethnic intolerance, and crime. This hindrance to the evolution of consciousness is a critical aspect of the tracking system in place within American society, thereby those designated the under-class are corralled, controlled, and channeled into delinquency, prison, and political/social death. It reduces human beings from subjects to mere objects in history.

This book, presented in the form of lessons, speaks to a history of racial and ethnic domination in Massachusetts, that intrudes upon the collective psyche of its citizens. It exposes a self-righteous veneer of white supremacy and manifest destiny—a legacy of puritan values—as perceived through the jaundiced eyes of the European majority and inflicted upon the state’s ethnic minorities in the name of explicit capital gain through domination. It is about the creation of an atmosphere of uncertainty and fear,(6) as the means by which to crush opposition and suppress change. It is about the history of America and what underlies her present day domestic and foreign policies. To emphasis this I chose, in places, to use the blended word “Massissippi,” referring to Massachusetts and Mississippi. The combination of an overtly racist former “Jim Crow” State and the occlusive systemic institutional racism of a New England State, to my mind, accurately defines the experiences that countless numbers have suffered and continued to endure. I explain this more fully in Appendix F.

My becoming BANTU, in service to NPRA, was not a single or solitary lesson. Rather, it was a evolution—an awareness of self in history, even as history was unfolding around me.

Ralph C. Hamm III

2016

NOTES:

1. Jamie Bissonette, When the Prisoners Ran Walpole: A True Story in the Movement for Prison Abolition, (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2008), p. 72-74.

2. Bissonette, Ibid., pp. 70-71; begin specifically, “On March 17, prisoners at Walpole rebelled against guard manipulation.”

3. Bissonette, Ibid., passim.

4. “He came to Boston a committed prison abolitionist dedicated to eradicating slavery in all its forms. He taught prisoners and allies crucial skills for engaging in the struggle.” Bissonette, Ibid., p. 13.

5. “In the first week after Hamm’s release from segregation, David Dance, a Harvard undergraduate active in the Black Panther support work in Boston, received the administration’s permission to start a black history course inside Walpole.” Bissonette, Ibid., p. 69.

6. “The oppressed are afraid to embrace freedom; the oppressors are afraid of losing the freedom to oppress.” Paolo Freire.

AMERIKlan JUST-US (MASSISSIPPI-STYLE)

If they came for me

before first light

on thanksgiving day morning,

with their christian hypocrisy

reflecting their might . . .

would you question

their means of injustice?

Would you care

who was wrong or right?

Or would you cower

behind closed doors,

and drawn curtains,

afraid to confront

their collective sight?

Allow those crosses to burn,

and then maybe, in turn,

they’ll come for you next

in the night.